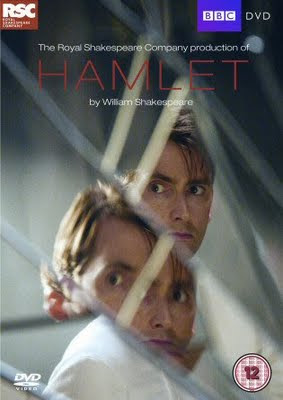

Richard Kelly as Rosencrantz.

Richard Kelly as Rosencrantz.

Simon Hedger as Guildenstern.

Directed by Max Rubin.

Utterly, utterly brilliant.

Before heading off into too detailed an explanation as to why the

Lodestar Theatre Company’s production is so utterly, utterly brilliant, it’s important to urge you, if you’re in the Liverpool area and you have an interest in theatre, however vague, to seek out this production before it goes forever on the 13th September. It’s at the

Novas Contemporary Urban Centre which you may not have heard of (the taxi driver who took me certainly didn’t), but if you can get to Caines Brewery, it’s opposite (ish) there.

Here’s a map and and

ticket details. If you manage to visit on 5th, 12th or 13th you will be able to see this show and their Hamlet (

previously reviewed) back to back.

Now onward.

Nominally, Tom Stoppard’s

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead is about what happens to these minor characters from Hamlet whilst the rest of the revenge tragedy is playing out, from their summons to untimely death. But rather than simply pouring in more plot, Stoppard wraps these journeymen around a structure heavily influenced by Samuel Beckett’s absurdest Waiting for Godot, unpacking the themes and structure of Shakespeare’s story to discuss the nature of chance, destiny and death and with the aid of the players throw in a meditation on the nature of acting and duality.

The writer isn’t interested in somehow giving G & R inner lives, but instead he creates two figures who find themselves in an impossible situation in which they’re dragged along until ultimately they die, trying to understand precisely what they did and what they could have done to change to outcome. It’s an existential puzzle, which to a degree mirrors reality more closely than a John Osbourne kitchen-sinker since we’re all drowning in a sea of questions which, depending upon your philosophical point of view, are given few answers.

And it’s a comedy. And I laughed like a drainpipe all night, big theatrical belly laughs. It’s to the credit of the actors that they weren’t distracted by my shaking about, head back, gob open, sitting on the front row, right in the middle. But I wasn’t the only one. The whole audience, guffawed and gaped, and oddly at different things. A line that went dead one side of the room became comic gold at the other, but often it was simply because you couldn’t laugh at everything. I’ve had a cold this week and it perked my right up, made me feel like myself again.

Sometimes, it was straight wit of the lines, sometimes the truisms, sometimes the commentary on the acting profession, sometimes the heroic criticism of Shakespeare’s poetry, particularly during Rosencrantz and Guildenstern’s first meeting with Hamlet, who as Stoppard points out offers a pack of lies and double talk which doesn’t get them anywhere and leaves them even worse off because the prince knows more about their state of mind than they do of his, proving the old theory from the studenty quiz show

Blockbusters that sometimes one head is better than two.

In this production it was also the delivery. In my review of Lodestar’s Hamlet, I gave Richard Kelly and Simon Hedger special mention and thankfully, brilliantly, given the duration of a whole play to work with and these lines, they combine to create a classic double act, with razor sharp timing, and a genuine sense of two people who’s friendship has spanned a lifetime, the Kelly’s empiric Rosencrantz forever undercut by the realism of Hedger’s Guildenstern. There are moments, as they hammer out the dialogue that the words aren’t just simply learnt lines hanging from their lips, but something they genuinely believe.

Kelly and Hedger are one of the best theatrical double acts I’ve seen, at least as tight as Rik Mayall and Ade Edmondson were in their classic production of Godot, if not more so since Kelly and Hedger (seemed at least) to lack the fear of doing something approximating classical theatre for the first time, the fear of getting it wrong. Stoppard’s dialogue isn’t easy. This isn’t idle hyperbole. There are sections, such as the linguistic tennis game, which must require supreme concentration, but these two make it look easy. The few occasions I wasn’t laughing, it was simply because I was enjoying the spectacle of two young actors at the top of their game.

The rest of cast aren’t anything to be sniffed at either. The other minor characters to be given feature status in Stoppard’s play are the players led in this production by Liam Tobin. A travelling troupe of tragedians, the irony is of course that the process of them parsing their craft is hilarious. Tobin’s player is a ringmaster, marshalling events, a disruptive influence whenever R & G give the impression of finally marking out an equilibrium in their chaotic world. In fact, all of the players have lashings of pathos; under Max Rubin’s direction their mockable very public under-appreciation slowly gains a poignancy as we eventually understand that if an actor is unable to successfully ply their craft, they are nothing. It’s a kind of death.

When the rest of the cast from the other production do sweep through it’s like greeting old friends. As I suspected, in this space, more intimate than the Concert Room at St George’s Hall, the actors an increased vitality, though in the transfer, the performances are more clipped, slightly caricatured, perhaps as a way of melding them into these slightly different circumstances. The effect of having already seen them in that earlier production is to have the other story, in the other setting, playing at the back of your mind, almost imagining as Claudius and Gertrude disappear from this stage, that they’re reappearing over there, before a different audience.

It must be rather strange for them to get into those same costumes, prepare themselves and then have to wait for a cue to present just a splinter of their previous performance, albeit reconfigured slightly in this new venue. Does Tom Latham, who plays Horatio, wait around all night, or just turn up half an hour before the end to give a reprise of his final big speech? Stephen Fletcher has the most difficult job, because at times he's an on-stage presence, maintaining Hamlet's epic intensity while his fellow cast members clown about, sometimes mocking that thing which defines his character in the other production.

The Wake Theatre at the Novas is a bit of an unlikely space; like the rest of the centre it’s built into an old warehouse, but resembles a cinema screen from the period before multiplexes brought in stadium seating. It’s what you’d expect a dedicated university theatre to be like, large enough to hold a student body greedy to see their classmates acting up, but small enough to hold classes. The props from the previous production reappeared here, a rich on-stage visual reminder of previous events, some, like Shakespeare’s characters, reduced to silhouettes by the atmospheric lighting and dry ice effects. Just another demonstration of how well conceived these productions have been and I look forward to seeing what Lodestar do next.

Any chance of a Measure for Measure?

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead is at at the Novas Contemporary Urban Centre until the 13th September 2009. Click here to buy tickets.

+wih+the+weird+sisters1.jpg)

+and+Macduff+(Kirk+Barker)+fight+to+the+death1.jpg)