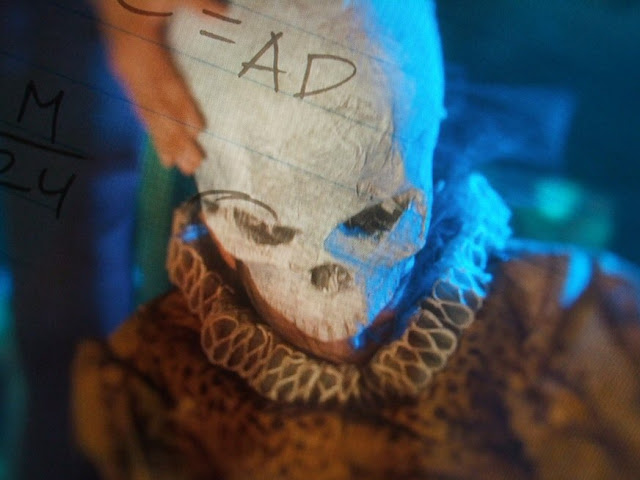

Schoolboy Oskar Schell sends himself on a mission to find the lock which fits a key he's found in the closet of his father who's recently died in 9/11. Days turn to weeks and eventually he's bursting to tell someone, that someone ultimately being "the renter", an elderly gentleman who lives with his grandmother. During one of the film's breathless montage sequences, he mentions the school's production of Hamlet:

It's a thematically pertinent choice as both Oskar and the Prince are experiencing the death of a parent in unbelievable circumstances. The removal of the the skull mask to reveal Oskar's face fits all the relevant iconography into the shot making it entirely recognisable especially since as the novel indicates, he's playing Yorrick rather than the Hamlet.

Hamlet has a much stronger presence in Jonathan Safran Foer's novel. Throughout Oskar mentions his Hamlet rehearsals and carries a copy of the script about with him on his quest, "so I could memorize my stage directions while I was going from one place to another, because I didn't have any lines to memorize".

In the film, Oskar notes that there are more people alive in the world now than have died in human history and that eventually there won't be enough places in the world to bury them. In the novel, he says instead "if everyone want to play Hamlet at once, they couldn't, because there aren't enough skulls."

The book also features a section about the resulting production, "it was actually an abbreviated modern version, because the real Hamlet is too long and confusing, and most of the kids in my class have ADD. For example, the famous "To be or not to be speech" [...] was cut down so that it was just "To be or not to be, that's the question."

This brief wiki is also worth reading for dialogue and thematic parallels: " Oskar, has a similar issue to the one represented in Hamlet's soliloquy - What is our purpose, what is the point to our life? After his father dies in 9/ll, Oskar struggles with why he should even live his life, What is the point of doing something if you could die tomorrow?"

Thursday, July 26, 2012

Thursday, July 19, 2012

Shakespeare Uncovered:

David Tennant on Hamlet

The story so far: Shakespeare Uncovered is a series of six introductions to plays introduced by leading actors and directors produced in association with the Globe theatre. The highlights have included Joely Richardson magically covered in snow during her first visit to the recreation of Shakespeare’s playhouse and discovering during Trevor Nunn’s exposition on The Tempest that there’s a recreation of Blackfriars in Staunton, Virginia. Less appealing is Sir Derek Jacobi’s ten minute detor into authorship madness during an otherwise informative introduction to Richard II and Ethan Hawke subtly damaging a First Folio by stroking his finger across a page and knocking out an existing burn mark leaving a hole, the text on the next page now clearly visible.

Now we reach David Tennant on Hamlet and although I’m biased the best of the episodes. Focusing on Hamlet’s struggle with his mission and his own mortality, David gallops through the story from the ramparts to “the rest is silence” aided by a number of fellow actors, academics and as he wanders about in the bridging cutaways the architecture of Stratford-upon-Avon and the Southbank, struggling with the question of why the play is still considered the pinnacle of English literature, the one secular text which continues to enthral and inform us as much as holy texts if not more so. But again, I would say that, I’m biased. Yet as Ben Whishaw notes for six months after playing Hamlet in 2004 he found himself applying all of life’s big questions and presumably some of the small ones to the play, recalling the text over and over. I do that too.

Utilising a synopsis of the play as a spine for observation is a fairly typical approach (cf, Imagine ... Being Hamlet and Playing the Dane, the inspiration for this blog), questioning the action at key points, with contributors providing their experiences of playing the part or analysing them. Because Hamlet is so thematically rich the producers have had to make similar decisions to a company producing the play so the focus is very much on the domestic elements, with little to nothing on the politics of Elsinore and Denmark, the succession. Fortinbras is cut. Lost too are Rosencrantz and Guidenstern other than the fact of their existence so nothing on the implications of their murder. “England” is generally glossed over. This is all about Hamlet’s personal j-word and those who’ve chosen to follow him.

All of which is perfectly understandable actually since entire books have been written about all of them, and there’s just an hour to play about with. It’s natural that you’d want to concentrate on the icons, whilst hinting at what lies beyond, the feigned madness, the implications of the willow scene that sort of thing. That’s especially true of the section shot at the Novell Theatre in which Michael Dobson offers a potted history of the closet scene which glanced towards Freud and also explains how Hamlet’s sometimes inappropriate attitude to his mother developed. Some productions almost treat the action in two discrete sections but as David notes there’s something very uneasy about Hamlet being so obsessed with Gertrude’s sex life with Polonius’s cadaver close by.

There are some unexpected inclusions. As with some of the other episodes, David was given the opportunity to see original copies of the text, in this case at the British Library and crucially all three versions including their copy of Q1 (one of only two in the world), comparing and contrasting the different versions of the big speeches and stage directions, discussing with curator of Early British Literature, Tim Pye the source of this earlier version. It’s worth noting that one of the potential weaknesses of the documentary is when David rhetorically asks who created this extraordinary character and where he came, we're not told about the Ur-Hamlet or Saxo Grammaticus but (admittedly touchingly) Shakespeare’s family and the death of Hamnet, which was also an influence on Twelfth Night in a very similar sequence in the Joely Richardson episode, one of the few occasions when the original source of a piece hasn’t been expounded upon.

Indeed, David has an impressively full participation, the episode’s presentation echoing his earlier presenter led episode of Doctor Who Confidential, “Do You Remember the First Time?” in which like this, he shared his affection for a much loved character whilst wearing a brown jacket. Then he visited the hallowed ground of Studio 8 of television centre, here it’s King Edwards Grammar Schoo, Shakespeare's school. Then he interviewed fellow fans like Steven Moffat and here we see him joshing over old reviews with David Warner and comparing approaches to the character with Jude Law. At least in terms of the language of television, my favourite interview might be with Simon Russell Beale who (like Whishaw) has appeared in nearly all of the episodes in interviews clearly shot all together and so it seems here until David asks a follow up question and camera whip-pans in his direction. Beale himself almost startled to suddenly have his fellow actor sitting there.

Like that Confidential, this features dozens of illustrative clips though interestingly limited to Olivier directing himself, Zeffirelli directing Gibson and understandably Doran directing Tennant. An early trip through the RSC shop with David indicates other versions are available, but these three are interesting choices in that they’re not traditional renderings of the text, Olivier adding some, Zeffirelli deleting practically everything and Doran shuffling the order of the scenes. Odd that we should have the Warner interview but not the clips of his RSC appearance seen elsewhere. As with the other episodes, the emphasis instead is on newly filmed sections performed by the Globe’s cast with Jack Farthing (pictured below) cutting a youthful, lonely figure in a near empty theatre during “To Be Or Not To Be..” and Tom Lawrence later a teary Horatio as his prince dies.

As well as David greeting Andrei Tchaikovsky's skull again (pictured) the most poignant section for me is right at the very end, when he’s pondering what the part means to him and startling it resonates with comments he made when he left Doctor Who. Indeed just for a moment (thanks to a reference to filming), I wondered which role he’s actually talking about:

"In the end, there’s just no other character like him. […] I remember on the last day of filming thinking, “I’m so proud to have done that. I’m so pleased that’s something I got to do. And now I will never go there again.” And there was a huge relief to that. It was like having a weight lifted off your shoulders. And then, where are we now? Three years on… I do find myself, I catch myself, slightly fantasising about doing it again, going back there and seeing what that would feel like. But … that way madness quite literally lies.”Fiftieth anniversary next year then.

[Assuming I haven't spoiled it too much for you, David Tennant on Hamlet is available on the iPlayer until 26th July.]

Thursday, July 12, 2012

The Shakespeare Cookbook by Andrew Dalby and Maureen Dalby.

Sometimes, just sometimes, I cry in supermarkets. This shouldn’t surprise regular readers who’ll know my emotion gland can be overwhelmed by the simplest of things. There’s a three-fold complexity to my feelings about supermarkets. Firstly, it’s the rudeness of fellow shoppers with barging tendencies unable to understand those like me with weak decision making skills. Secondly it’s my lack of decision making skills and wanting to taste everything despite there only being three meals in a day and seven of those days between shopping trips.

But thirdly, and primarily it’s what supermarkets represent. Weeping in the cheese aisle amongst the crumbly varieties with county names, the Lancashires, Cheshires, Cheddars. I thought about the history of those cheeses, the heritage and how centuries of tradition now sit wrapped in plastic for our convenience with labels designed to attract us with an idealised version of the history, the heritage, the centuries of tradition. The answer is to purchase such at farmers markets, but supermarkets are convenient, which also make me inadequate.

Unfortunately The Shakespeare Cookbook by historian Andrew Dalby and cook Maureen Dalby goes some way to increasing that inadequacy, since although I’m not necessarily a terrible cook I’m an unpractised one which means there’s little chance of the recipes listed being anything like the mental pictures they conjure (another reason for the supermarket tragedy). Luckily then, it’s much more than that, the authors utilising a number of contemporary sources to offer a taste (sorry) of eating habits and favourite dishes in the Elizabethan and Jacobean periods.

The Shakespeare connection involves ransacking the plays and their sources for food references and extrapolating those out into explanations for the surprisingly large variety of dishes which were available in the period, some of which are now available in supermarkets but many entirely alien to our tastebuds, though it’s almost disappointing Baxters don’t produce a tinned variety of Swan Chauder. As well as quoting from a variety of cookbooks (most of them now available online), the authors also provide contemporary equivalents for modern chefs to try.

For Hamlet, that’s the feast Hamlet refers to when question Horatio on his appearance in Elsinore, “Thrift, thrift, Horatio. The funeral baked meats / Did coldly furnish forth the marriage tables.” The Dalbys aren’t sure if the prince is speaking literally but we’re quickly introduced to the food he’s referring to, “cooked meats” being pies, the pastry cases before filling fittingly, given the themes of the play, called “coffins”. We’re then provided with recipes for hot water crust pastry and shortcrust pastry neither of which seem that complicated even though they undoubtedly are.

Given my culinary inadequacy I’m probably not the best judge of whether this works as a cookbook. Structurally it’s unusually set out, with chapters themed around various plays with a short introduction focusing on various textual victuals, either metaphoric or consumed on stage followed by short pieces explaining these various elements, some more tenuous than others. Would a serious foody want these recipes to be more conventionally clustered around the usual headings, starters, meat dishes, fish dishes, deserts and drinks?

But if the book has a particular strength its that it doesn’t just rely on Shakespeare for illustrative quotes featuring when necessary works by his contemporaries, with Middleton’s The Witches allowing us to see what may have been on the Macbeth’s table during Banquo’s visitation and a rousing speech from Maid Marion in Jonson’s unfinished Robin Hood play The Sad Shepherd providing a glimpse of the Bohemian sheep-shearing feast in A Winter’s Tale. And when that fails they quote from Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall, which shows an eclectic attention to detail.

Whether any of this will improve or deteriorate further my ability to visit supermarkets without it becoming some great personal tragedy will be hard to tell. Perhaps the trick will be to select a recipe at random, wait a moment, yes, hodgepot, gather the ingredients and make an attempt. The authors replace marigold flowers with saffron so that seems perfectly doable. Perhaps I’ll report back. But until then at least when I see marchpane, or rather marzipan on the shelf, I’ll know it’s always been a convenience food, even in Shakespeare’s day.

The Shakespeare Cookbook by Andrew Dalby and Maureen Dalby is out now from the British Museum Press. RRP £10.99. ISBN: 978-0714123356. Review copy supplied.

But thirdly, and primarily it’s what supermarkets represent. Weeping in the cheese aisle amongst the crumbly varieties with county names, the Lancashires, Cheshires, Cheddars. I thought about the history of those cheeses, the heritage and how centuries of tradition now sit wrapped in plastic for our convenience with labels designed to attract us with an idealised version of the history, the heritage, the centuries of tradition. The answer is to purchase such at farmers markets, but supermarkets are convenient, which also make me inadequate.

Unfortunately The Shakespeare Cookbook by historian Andrew Dalby and cook Maureen Dalby goes some way to increasing that inadequacy, since although I’m not necessarily a terrible cook I’m an unpractised one which means there’s little chance of the recipes listed being anything like the mental pictures they conjure (another reason for the supermarket tragedy). Luckily then, it’s much more than that, the authors utilising a number of contemporary sources to offer a taste (sorry) of eating habits and favourite dishes in the Elizabethan and Jacobean periods.

The Shakespeare connection involves ransacking the plays and their sources for food references and extrapolating those out into explanations for the surprisingly large variety of dishes which were available in the period, some of which are now available in supermarkets but many entirely alien to our tastebuds, though it’s almost disappointing Baxters don’t produce a tinned variety of Swan Chauder. As well as quoting from a variety of cookbooks (most of them now available online), the authors also provide contemporary equivalents for modern chefs to try.

For Hamlet, that’s the feast Hamlet refers to when question Horatio on his appearance in Elsinore, “Thrift, thrift, Horatio. The funeral baked meats / Did coldly furnish forth the marriage tables.” The Dalbys aren’t sure if the prince is speaking literally but we’re quickly introduced to the food he’s referring to, “cooked meats” being pies, the pastry cases before filling fittingly, given the themes of the play, called “coffins”. We’re then provided with recipes for hot water crust pastry and shortcrust pastry neither of which seem that complicated even though they undoubtedly are.

Given my culinary inadequacy I’m probably not the best judge of whether this works as a cookbook. Structurally it’s unusually set out, with chapters themed around various plays with a short introduction focusing on various textual victuals, either metaphoric or consumed on stage followed by short pieces explaining these various elements, some more tenuous than others. Would a serious foody want these recipes to be more conventionally clustered around the usual headings, starters, meat dishes, fish dishes, deserts and drinks?

But if the book has a particular strength its that it doesn’t just rely on Shakespeare for illustrative quotes featuring when necessary works by his contemporaries, with Middleton’s The Witches allowing us to see what may have been on the Macbeth’s table during Banquo’s visitation and a rousing speech from Maid Marion in Jonson’s unfinished Robin Hood play The Sad Shepherd providing a glimpse of the Bohemian sheep-shearing feast in A Winter’s Tale. And when that fails they quote from Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall, which shows an eclectic attention to detail.

Whether any of this will improve or deteriorate further my ability to visit supermarkets without it becoming some great personal tragedy will be hard to tell. Perhaps the trick will be to select a recipe at random, wait a moment, yes, hodgepot, gather the ingredients and make an attempt. The authors replace marigold flowers with saffron so that seems perfectly doable. Perhaps I’ll report back. But until then at least when I see marchpane, or rather marzipan on the shelf, I’ll know it’s always been a convenience food, even in Shakespeare’s day.

The Shakespeare Cookbook by Andrew Dalby and Maureen Dalby is out now from the British Museum Press. RRP £10.99. ISBN: 978-0714123356. Review copy supplied.

Labels:

british museum

Wednesday, July 11, 2012

Shakespeare's Restless World.

Hats! What’s often forgotten about Hamlet is that amongst the psychological introspection and political intrigue, the prince’s headgear is a vital element in broadcasting his madness, feigned or otherwise, and one of the triggers which leads to Polonius’s investigation of his psychological well being. It was not just a tradition but law, from a parliamentary statute of 1571, that all men in society to wear caps and they became an important part of confirming social divisions.

If someone wasn’t wearing their headgear it was a pretty good indication that they weren’t well, so when Ophelia notes to her father “My lord, as I was sewing in my closet, / Lord Hamlet, with his doublet all unbraced, / No hat upon his head…” it suggested the privy councillor and us that something is terribly wrong with the young prince. Arguably it could also indicate there’s something terribly wrong with the production if that line’s in there and no one else is behatted in some way.

Broadcast a few months ago on Radio 4 and now out on cd, Shakespeare’s Restless World, one of the epicentres of the BBC’s year long coverage of the bard’s work, seeks to investigate his plays, his life and his world through the objects of the British Museum and further afield. Presented by Neil MacGregor, director of the museum, it’s an audio adjunct to the Shakespeare: staging the world exhibition (part of the cultural Olympiad) in the style of his previous History of the World in 100 Objects.

As with that series, the objects are really enry points into exploring a particular aspect of the Elizabethan and Jacobian world and so a rather anonymous apprentice’s cap inspires a discussion of the class system, social propriety and rioting, feeding into the series other aim of finding parallels with contemporary Britain. In another episode MacGreggor indicates chillingly it was quite natural then as now for young men to carry knives around ready to defend themselves.

These twenty episodes do cover similar ground to the catalogue which accompanies the British Library’s exhibition but there’s a much greater, perhaps more convincing effort to link the objects to Shakespeare’s plays. When considering The Stratford Chalice in the second programme in relation to the country’s religious strife as a symbol of the new Protestant faith, he explains that the language in the Ghost of Hamlet Snr's speech is of the old religion, of the old ways.

Sometimes the themes and objects have been selected to indicate what isn’t in the plays. In an episode about Plague Proclamations, we’re reminded that even though pestilence was prevalent in the period and a massive influence structurally on Shakespeare’s career, as far as we know no plays were written on the topic and it was barely mention in the canon except for briefly in Romeo and Juliet. Quite a contrast from public executions which were bloodily dramatised.

The list of contributors is smaller than A History of the World, relying on some of the usual academics like Bate and Shapiro along with curators across the country who handle the objects like Jan Graffius, curator of the Stonyhurst collection who hold the Oldcorne Reliquary. In an episode about duelling, Alison de Burgh, Britain's first female theatre fight director entertainingly teaches MacGreggor how to hold his own. Luckily, has he says "Health and Safety regulations kicked in and stopped her killing me”.

Threaded throughout the episodes are a collection of excepts from the plays brilliantly read by the likes of David Warner, Chiwetel Ejiofor and Rory Kinnear. In episode two there’s a brief part of the duel scene in which Don Warrington gives us his Claudio, and we also later hear the aforementioned closet flashback. Frustratingly a cast list isn’t included in the accompanying booklet (or a full list of contributors for that matter) but then that doesn’t include images of all the objects either.

But, other than duration, it's too short, that’s about the only criticism I have of this fascinating release which constantly surprises with its nuggets of tangential information and enthralling stories. The Shakespeare’s Restless World website of course has all the episodes to listen to again, download as podcasts and complete transcripts so you might question what’s to gained from buying the cds. But for collectors of Shakespeareana they’re probably essential.

Shakespeare's Restless World is out now from AudioGo. Review copy supplied.

If someone wasn’t wearing their headgear it was a pretty good indication that they weren’t well, so when Ophelia notes to her father “My lord, as I was sewing in my closet, / Lord Hamlet, with his doublet all unbraced, / No hat upon his head…” it suggested the privy councillor and us that something is terribly wrong with the young prince. Arguably it could also indicate there’s something terribly wrong with the production if that line’s in there and no one else is behatted in some way.

Broadcast a few months ago on Radio 4 and now out on cd, Shakespeare’s Restless World, one of the epicentres of the BBC’s year long coverage of the bard’s work, seeks to investigate his plays, his life and his world through the objects of the British Museum and further afield. Presented by Neil MacGregor, director of the museum, it’s an audio adjunct to the Shakespeare: staging the world exhibition (part of the cultural Olympiad) in the style of his previous History of the World in 100 Objects.

As with that series, the objects are really enry points into exploring a particular aspect of the Elizabethan and Jacobian world and so a rather anonymous apprentice’s cap inspires a discussion of the class system, social propriety and rioting, feeding into the series other aim of finding parallels with contemporary Britain. In another episode MacGreggor indicates chillingly it was quite natural then as now for young men to carry knives around ready to defend themselves.

These twenty episodes do cover similar ground to the catalogue which accompanies the British Library’s exhibition but there’s a much greater, perhaps more convincing effort to link the objects to Shakespeare’s plays. When considering The Stratford Chalice in the second programme in relation to the country’s religious strife as a symbol of the new Protestant faith, he explains that the language in the Ghost of Hamlet Snr's speech is of the old religion, of the old ways.

Sometimes the themes and objects have been selected to indicate what isn’t in the plays. In an episode about Plague Proclamations, we’re reminded that even though pestilence was prevalent in the period and a massive influence structurally on Shakespeare’s career, as far as we know no plays were written on the topic and it was barely mention in the canon except for briefly in Romeo and Juliet. Quite a contrast from public executions which were bloodily dramatised.

The list of contributors is smaller than A History of the World, relying on some of the usual academics like Bate and Shapiro along with curators across the country who handle the objects like Jan Graffius, curator of the Stonyhurst collection who hold the Oldcorne Reliquary. In an episode about duelling, Alison de Burgh, Britain's first female theatre fight director entertainingly teaches MacGreggor how to hold his own. Luckily, has he says "Health and Safety regulations kicked in and stopped her killing me”.

Threaded throughout the episodes are a collection of excepts from the plays brilliantly read by the likes of David Warner, Chiwetel Ejiofor and Rory Kinnear. In episode two there’s a brief part of the duel scene in which Don Warrington gives us his Claudio, and we also later hear the aforementioned closet flashback. Frustratingly a cast list isn’t included in the accompanying booklet (or a full list of contributors for that matter) but then that doesn’t include images of all the objects either.

But, other than duration, it's too short, that’s about the only criticism I have of this fascinating release which constantly surprises with its nuggets of tangential information and enthralling stories. The Shakespeare’s Restless World website of course has all the episodes to listen to again, download as podcasts and complete transcripts so you might question what’s to gained from buying the cds. But for collectors of Shakespeareana they’re probably essential.

Shakespeare's Restless World is out now from AudioGo. Review copy supplied.

Labels:

audiogo,

shakespeare at the BBC

David Tennant on Hamlet scheduling update.

Yes, this is an important scheduling reminder/update for the final Shakespeare Uncovered documentary and most important to this parish, David Tennant on Hamlet. For some ungodly reason, the BBC have decided that far from appearing after The Hollow Crown on Saturday presumably because it doesn't have a thematic connection or in the slot some of the shows had on BBC Four because it's David Tennant on Hamlet, they've seen fit to broadcast it on ...

Tuesday 17th July at 11:20pm after Newsnight

that's ...

Tuesday 17th July at 11:20pm after Newsnight

Exactly why this isn't on after The Hollow Crown is beyond me. For one thing it's the episode for which you'd think there was a built in audience even after a couple of years and for another the expected timeslot has instead a QI repeat and half a rerun of a TOTP.

Tuesday 17th July at 11:20pm after Newsnight

that's ...

Tuesday 17th July at 11:20pm after Newsnight

Exactly why this isn't on after The Hollow Crown is beyond me. For one thing it's the episode for which you'd think there was a built in audience even after a couple of years and for another the expected timeslot has instead a QI repeat and half a rerun of a TOTP.

Labels:

david tennant,

shakespeare at the BBC

Saturday, July 07, 2012

For Schools: Hamlet screened the BFI.

On the Sceenplay's blog, John Wyver reports on the BFI screening of For Schools: Hamlet, the 1961 ITV series starring Barry Foster in the title role:

"Jennifer Daniel is a posh Ophelia who fails to convince in the ‘mad’ scene. As Gertrude Patricia Jessel, who had been a regular at the Stratford Memorial Theatre since 1944, has a rather remarkable neck, but she falls short in the ‘closet’ scene. The best of other players is probably Sydney Tafler as Claudius, another criminal role to add to the actor’s tally in British noir films of the previous decade."This was thought lost for many years until a copy was found in the Library of Congress and returned to the BFI. For all John's reservations, let's hope an accessible edition (streaming perhaps since a home release seems unlikely) is made available soon.

Labels:

barry foster,

bfi,

eyewitnesses

Wednesday, July 04, 2012

Shakespeare on Spotify: Rare Marlowe Players production of Hamlet with Patrick Wymark.

An amazing rarity has cropped up on Spotify. Based on the various parts of editions I've collected, my understanding has always been that the production of Hamlet included in the Argo imprint was this recording of the Old Vic Company production with Derek Jacobi. That hasn't always sat well with me though, especially since the others were recorded with the Marlowe Society in conjunction with the British Council and it seemed strange that such an arrangement wouldn't also include the greatest play, especially since they also polished off King Lear.

Now the mystery's been solved:

Now the mystery's been solved:

Sunday, July 01, 2012

Shakespeare and me in The Observer

Today's Observer has a special section, Shakespeare and Me in which various actors and directors talk about the plays have effected them. There's plenty of Hamlet interest.

Simon Russell Beale: "I think it was the actor Paul Rhys who said to me: "Hamlet will change you", and I didn't believe him. He was right, though – it's the only part you can't hide behind – and you spend most of the time contemplating your death, which is quite hard to do when you're 40, not yet ancient."

Judi Dench: "I made my professional debut as Ophelia in 1957. I didn't know enough to be daunted by it at the time. I learnt an incredible amount from it. My notices were certainly daunting. You learn from them – you learn very soon. You just have to grit your teeth and get on and learn to do it better."

Alan Cumming: "It probably wasn't a great idea to play Hamlet opposite my ex-wife [Hilary Lyon] as Ophelia. We were coming towards the end of our marriage and I pretty much had a full-on breakdown after it. The play also dredged up some awful things with my father, and I realised there were a lot of unresolved issues in my life that I needed to deal with."

Michelle Dockery: "Anyone who's ever played Ophelia should all get together for a big group hug. I played Ophelia with John Simm at Sheffield and I began to suffer terrible insomnia in the same way that Hamlet does. It's such a tough part and Ophelia is a huge leap, especially in the end, when she descends into her madness."

But the whole thing's a pleasure and all available here.

Simon Russell Beale: "I think it was the actor Paul Rhys who said to me: "Hamlet will change you", and I didn't believe him. He was right, though – it's the only part you can't hide behind – and you spend most of the time contemplating your death, which is quite hard to do when you're 40, not yet ancient."

Judi Dench: "I made my professional debut as Ophelia in 1957. I didn't know enough to be daunted by it at the time. I learnt an incredible amount from it. My notices were certainly daunting. You learn from them – you learn very soon. You just have to grit your teeth and get on and learn to do it better."

Alan Cumming: "It probably wasn't a great idea to play Hamlet opposite my ex-wife [Hilary Lyon] as Ophelia. We were coming towards the end of our marriage and I pretty much had a full-on breakdown after it. The play also dredged up some awful things with my father, and I realised there were a lot of unresolved issues in my life that I needed to deal with."

Michelle Dockery: "Anyone who's ever played Ophelia should all get together for a big group hug. I played Ophelia with John Simm at Sheffield and I began to suffer terrible insomnia in the same way that Hamlet does. It's such a tough part and Ophelia is a huge leap, especially in the end, when she descends into her madness."

But the whole thing's a pleasure and all available here.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)